GREENVILLE — Jamison Meade, an 11-year-old student in the fifth grade at Greenville Middle School, can only read at a first-grade level.

According to Jamison’s parents, he’s been receiving various services from the Greenville school system for years, including tutoring after school and one-on-one help during most classes. As Jamison prepared to start the fifth grade, however, his parents were told that his Individualized Education Program (I.E.P.) – a legally mandated document provided for students receiving special education services, spelling out the child’s needs, services the school will provide, and how progress will be measured – would go away as he transitioned into middle school.

The only accommodation Jamison would receive from that point on, his parents were told, would be an extra ninth-period study hall at the end of each school day.

Jamison has dyslexia. According to the International Dyslexia Association, dyslexia is a learning disability resulting in difficulty with specific language skills, especially reading. This can lead to difficulties with written and oral communication as well. According to the Dyslexia Center of Utah, one in five students has a language-based learning disability, of which dyslexia is the most common variety. As many as 80 percent of people with poor reading skills are likely dyslexic.

“Jamison is smart, intelligent, and respectful, but he has to learn in his own way,” Jamison’s mother, Andrea Boyd, said. “He gets to school at 7:30 in the morning, then has tutoring until five or six in the evening. Then he works on homework. It’s his whole day. He has no chance to relax or play.”

Ohio law does not recognize dyslexia as a specific disorder requiring specific interventions, so kids like Jamison are typically considered to have a “reading disability.” The standard response when a child is determined to have a reading disability is to develop an I.E.P., which is then reviewed periodically by the teachers and school officials involved to determine whether the child is making progress.

But if a child in the fifth grade is only reading at a first-grade level after years of interventions, how much progress is being made?

Andrea Townsend, director of Career Technology and Special Education at Greenville City Schools, explained a bit about how the process works.

“State and federal laws mandate the sort of services schools can provide,” Townsend said. “So while a student can’t qualify for help with dyslexia, specifically, they can qualify for group and one-on-one help with a reading disability.”

Townsend spoke passionately about her desire to help students and families struggling with learning disabilities.

“I want very much to be an active member of the team when it comes to making sure these students’ needs are being met,” Townsend said. “I want the family to feel supported, and I want the student to feel successful in school.”

Townsend and Greenville City Schools superintendent Douglas Fries insisted the incident where the Boyds were told Jamison had “aged out” of his I.E.P. was the result of a misunderstanding, and that in fact, students remain eligible to receive I.E.P. assistance, in special cases, until the age of 22. After a meeting between Townsend and the Boyds, Jamison’s I.E.P was reinstated.

But according to Mary Jo O’Neill, an advocate working with parents of children with dyslexia and other learning disabilities in the Cleveland, Ohio area, this is only half the battle.

“Why did the parents walk away with the wrong information in the first place?” O’Neill asked. “Why was that mother allowed to walk out believing her child’s services had been taken away? That’s disturbing to me.”

O’Neill believes that in many schools, while teachers and school officials may be well-meaning and good at their individual jobs, they don’t work together effectively in order to execute the complicated I.E.P. process.

“They’re not working together. They’re all working on their own little island,” O’Neill said. “Services aren’t being offered fluidly throughout the curriculum.”

For instance, according to O’Neill, an Intervention Specialist – an educator specially certified to deal with students struggling with learning disabilities – may be vital in helping a student to articulate their ideas and understand course instructions during the period when the two are working together, but the specialist isn’t there in class later, when the student is actually trying to write. This can affect performance in math, science, and social studies courses as well.

“The I.E.P. needs to be administered fluidly throughout the academic day,” O’Neill said. “Not in isolation.”

Meanwhile, even with the restoration of his I.E.P., Boyd isn’t confident the school has a long-term plan for her son’s academic progress.

“What are these kids supposed to do when they graduate?” Boyd asked. “They can’t read a job application. They can’t read a road sign.”

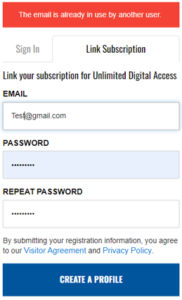

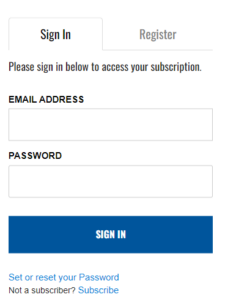

Parents searching for resources for kids with dyslexia can begin by visiting the Ohio Board of Education website at education.ohio.gov.