“Grunts” was a common expression used during the Vietnam War as a label for the U.S. military men who were lowest in the hierarchy of those who served. I decided to write about one of these men, Gary Unger, who did not die in that war and who did not receive two Purple Hearts for being grievously wounded there.

In San Antonio, Texas, is the Vietnam Army Grunt Museum. Under a heading at the museum website is a question “Who is a Vietnam Grunt?” which indicates for the uninformed what these men did in that war. The grunts among my readership already know:

It meant leaping out of helicopters unto landing zones that were sometimes under enemy fire. It meant marching through elephant grass taller than a man and as sharp as a knife or slogging across streams and rivers so deep and muddy that sometimes men disappeared beneath the surface or found themselves mired in mud so thick it sucked the boots off their feet. It meant suffering from heat, humidity, rain, and insects while straining under the burden of equipment which could weigh as much as 80 pounds. It meant enduring endless marches up and down mountains, through jungles and into villages, looking for an enemy who was hard to find and sometimes even harder to fight, all the while on the lookout for booby traps and ambushes.

With an average age of 19, these soldiers were sent to a country they called Nam, a place most could not locate on a map, to fight a war being directed by men whose names they didn’t know.

But they went; they served; they have stories.

Gary Unger of Troy, Ohio, a 1964 graduate of Franklin-Monroe High School in Darke County, Ohio, was drafted in March 1966. Following basic training at Fort Knox, he had jungle training at Fort Polk where he was trained on the firing range and the use of a compass and learned the strategies for recognizing booby traps. His squad was usually the first to go into a village, and he had been trained to as he indicates, “Always keep aware of my surroundings, trust no Vietnamese, and pray.” He says, “I had lots of anxiety and to tell you the truth, I was scared to death. The enemy would pop up like ghosts, ping, ping, and be gone.”

As an infantryman, he carried an M-16 rifle with a night-vision scope, 60 pounds of gear, and at times a machine gun.

He and his unit were transported to kill zones in two and one-half ton trucks. At a particular location, they jumped off the truck, ran into the jungle taking care to never traverse on trails or roads, and used their machetes to cut through the brush (Learning to use a machete was easy for Unger as he had used a similar device to cut tobacco on the farm where he was raised, and his father kept the devices razor sharp).

On one such mission, two of the men he was with were killed, three were wounded, and one suffered a concussion. He, thus, learned early on the dangers associated with his role in Vietnam.

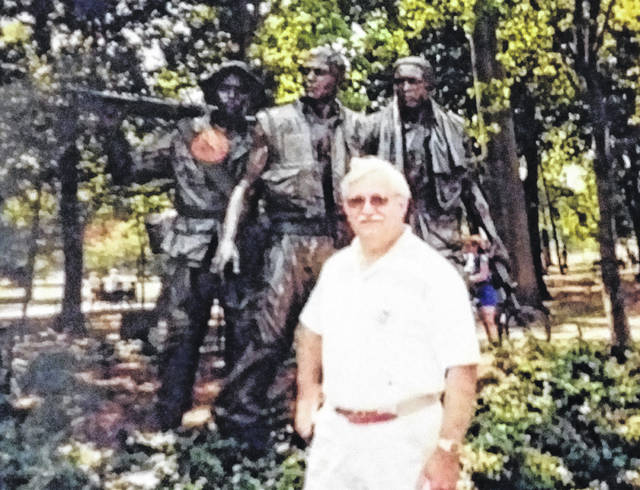

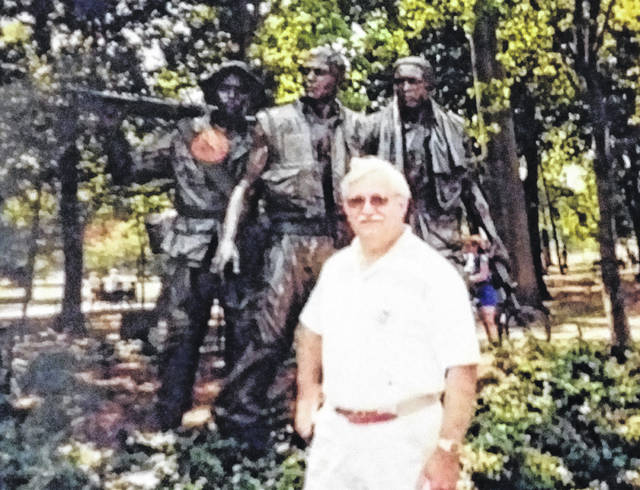

With deep sadness, Unger says, “Vietnam should never have happened. We were so brainwashed in jungle training as we were told they needed our help, that we didn’t want to be Communists. I have survivor’s guilt and have been to the Wall to see the names of the men I knew who died there.”

He continues, “We had a different operation every month with a different name for each, and I went on 10 the year I was there. The worst was Operation Billings in June of 1967. Our motto was ‘No mission too difficult. No sacrifice too great. Duty first.’

“We were close to the Cambodian border when we ran into a large group of Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese Army. The Green Berets had gone in before us to scout what was there. We were choppered into a landing zone by little Hueys that held a squad of eight with door gunners on the copters.

“During the mission, we just cried and kept on moving, telling ourselves that this wasn’t real, that this was a dream.

“We were joined by the First Battalion of the 16th Infantry. After the huge firefight, as we checked out the 344 dead enemies, we discovered 112 bunkers, eight base camps, and two wells.

“When it was over and we were back at base camp, I felt anxious. It all happened so quickly. The enemy was like ghosts. We really couldn’t see them. When they returned fire, we fired back. As some lay dying, we heard them scream, ‘GI, go home.’ I got the Bronze Star for that mission.”

A Postscript: The Vietnam War is over, but is it ever over? When Unger sees a man in a grocery store wearing a cap or jacket with the Vietnam War emblem, he asks, “What year were you there?”

And when his friend Jim Miller, a pilot in Vietnam, and he are working out at a fitness center, they talk about their war, that one in Vietnam, the one in a country Unger had to look up on a world map, the war where Unger says of the men who trained him, “They were good men, honest about what the book says but miles away from reality. They told us to stay off drugs that would mess our minds up but that we could get from any Vietnamese kid on the base. There was so much they couldn’t tell us. It was tougher than I thought it was going to be although some weeks it was just a little sniper fire.”

And then Unger says to Miller, “You know what we called you when we were in the hot LZ area and you came?”

Miller responds, “I’m afraid to ask.”

Unger says, “We called you our guardian angels.”

In conclusion, in this week as we have just celebrated our nation’s independence, I say, “On behalf of a grateful nation, thank you, Gary Unger and Jim Miller.”