GREENVILLE — As we walk through cemeteries this weekend we may note with reverence those who have served at particularly significant times in our nation’s history. We might wonder how the individuals experienced those long ago times and if they encountered the personages that we read about in our history books. One such person who raises these thoughts is William Patrick Dugan.

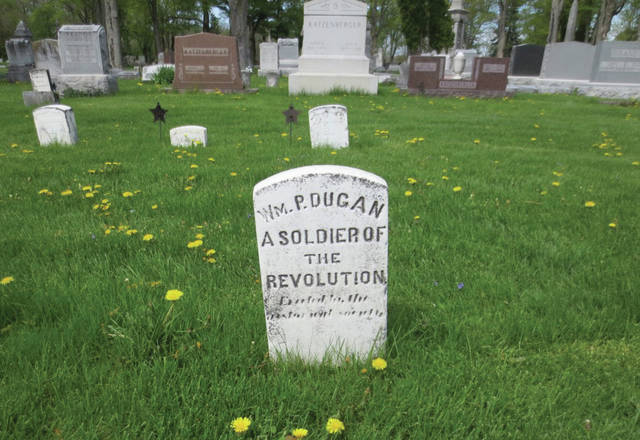

Dugan’s headstone clearly identifies him as a Soldier of the Revolution so that we are prompted to contemplate his service-related experiences during the birth pangs of our great nation. Fortunately, a good deal of information is available about his life during the war.

Born in Ireland about 1760 Dugan was probably 16 years old when he enlisted in the 3rd New Jersey Infantry Regiment in March of 1777. His pension record shows that he fought in battles at Brandywine, Germantown, Monmouth and several smaller engagements.

At Brandywine, Pennsylvania on Sept., 11, 1777 the 3rd New Jersey was tasked with delaying the advance of General Knyphausens’s Hessians along the pike from Kennett square to Chadd’s Ford, a six-mile movement. They did this by engaging in hit and run tactics, removing planks from bridge roadbeds, and cutting down trees to block the road. This invading force was under constant attack for three hours and took 50 percent casualties. When English forces later attacked the right wing of the Continental army the battle was essentially over. But Dugan’s unit had performed admirably and retired only when the main army had been put to flight. This British victory allowed them to take Philadelphia on September 26.

On October 4 the Americans caught the British unawares and with a massive effort drove back the forces in Germantown, Pennsylvania. Here, William Dugan and the New Jersey Brigade participated in the battles iconic image; the assault on the Chew mansion. About 120 British soldiers barricaded themselves inside the mansion and the

Americans made the mistake of throwing repeated assaults against the building instead of carrying forward with their attack. The result of this effort was the loss of over 70 men and a counterattack that swept the Americans from the field. Among the attackers, and perhaps rubbing shoulders with Dugan was John Marshall, future Chief Justice of the Supreme Court – the man who was to be largely responsible for defining the role of the Supreme Court in our government.

The next historical event where we find Dugan is the encampment at Valley Forge. On Dec. 19, 1977 some 12,000 American soldiers took up residence on the heights above Valley Forge where they could protect themselves from surprise British attacks while keeping a protective eye on the surrounding country.

Much has been written about the privations that the soldiers endured while at Valley Forge, but the most important result of the encampment was the transformation of the men from an unruly rabble to a fighting force capable of going toe-to-toe with the finest army in the world. This transformation was due in no small part to the efforts of General Friedrich Baron von Steuben. He instituted training methods that allowed for rapid dissemination of military procedures to the fighting men. Later he wrote the first training manual for the American army. We can be sure the Dugan was very familiar with Von Steuben as well as all of the senior American officers present at Valley Forge.

Once the winter of 1777-1778 ended the army was fit for combat against the British army. In early May the French entered the war on the side of the Americans. This development immediately changed the complexion of the war so that the British had to withdraw from Philadelphia and consolidate their forces in New York.

On June 28, 1778, while the British were on the road to New York, Washington moved on their rear at Monmouth Courthouse, New Jersey. Again the 3rd New Jersey regiment and Dugan set about hit and run tactics, blocking roads by cutting down trees, and destroying bridges. The day was extremely hot so the Americans added the tactic of filling in wells. This caused great distress to the British troops.

At one point the New Jersey Brigade was formed in line of battle facing advancing enemy troops. Their brigade and another were required to realign their men to meet this advance. Other units saw the dust kicked up by the movement and assumed that a retreat was underway. These units began retiring as well. General Marquis de Lafayette was about to attack the British in a deadly flanking move when the retreat cut short his plans and he also withdrew.

So it was that Dugan’s New Jersey regiment had an accidental role in turning an American victory into a draw. Even so, during the following night the British vacated the field of battle and continued to New York. The New Jersey regiments were tasked with swarming about the flanks of the lumbering British army all the way to New York.

In his pension file Dugan mentions that he was also involved in some smaller engagements. It is likely that this cryptic reference is to the Sullivan Expedition. On May 31, 1779, General Washington gave General Sullivan the New Jersey and Pennsylvania Brigades and other troops with instructions to invade Iroquois lands and ruin their crops and destroy their villages. This action was necessary due to the alignment of Six Nations of the Iroquois with the British. These Six Nations had been harassing the settlers on the frontier and were posing a threat to the security of the entire New York area.

Dugan completed his three year enlistment in March of 1780 and returned to his home in Morristown, New Jersey. By 1790 he had made it to Kentucky and eventually to Cincinnati, to Lemon Township in Butler county, and finally to Greenville in about 1819.

When Dugan died in 1851 he was 91 years old and had earned the probably honorary title of Major among the citizenry. He was buried in the Old Water Street Cemetery but was later re-interred in the Greenville Union Cemetery in the veteran’s section. This occurred in 1901 and “appropriate services” were planned for the next Memorial Day.

Here, in the person of one insignificant soldier, was the story of our nation’s founding. An immigrant from the beginning, he witnessed the events leading to the Declaration of Independence, he was there when the war began and served with honor in key battles of the war. During the war he saw and perhaps knew important persons in our history including the first President, the fourth Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, and the man responsible for making a real army out of gangs of farmers and villagers. He also must have known, or knew by sight, Alexander Hamilton (Washington’s aide), Lafayette, Molly Pitcher (Mary Hays), and many well known generals who served during this period.

We have to stand in awe at the things that our early settlers in Ohio and Greenville did, and that they did it without fanfare. We owe our veterans a special debt of gratitude that cannot be repaid. Each Memorial Day it is the least that we can do to pause for a moment and meditate on the unknown deeds and contributions of those whose graves we are viewing. Through the actions of these common people our country was born and continues to thrive.