As a freelance writer in 1979, I accompanied a photographer to interview sheepherders out west. These hardy workers stayed with the flock six weeks, visited by camp tenders who brought food, radio batteries, mail, and a single bottle of Early Times to them.

On Christmas Day I had an appointment to interview a female herder as she kept watch over her sheep in northwest Wyoming. But something inside her snapped in isolation. She quit to return home to West Virginia.

I learned this bad news from her rancher boss the morning of Dec. 24.

I explained the problem to photographer Max Aguilera Hellweg.

Two days earlier, we had profiled 38-year-old JaVoan Brantner. She herded sheep near the Bitterroot Range along the Continental Divide in an area known as Gobbler’s Lookout.

She wore a cast because a bear spooked her horse Cinnamon and resulted in a broken leg. A former nurse, she said her old job had grown pointless because some hospital administrators put emphasis on making money, not caring for people. “I wrapped a lot of [dead] bodies in shrouds,” she told me. “I noticed no pockets.”

In the pickup’s camper, we studied an atlas, picking out the town of Gardiner, Mt., as a place to regroup before the next scheduled magazine interview on Dec. 26.

Snow settled on the camper of my truck as Max and I drove through the lonesome country. Outside Gardiner’s city limits, antelope fed in a fenced pasture, eating hay for livestock put down by ranchers.

I parked the truck in front of a restaurant near the northern entrance to Yellowstone Park. I asked the waitress at the register if she could recommend cheap lodging.

“I’d try the Open Arms Motel,” she said.

“That’s its name?” Max asked.

“Not its real name,” she said. “A couple hippies run it. If people can’t afford the price of a room, they wait until 11 p.m. The owners let them stay free if they have a vacancy.”

The sign in front of a three-story home-turned-motel indicated vacancies existed. Hellweg and I paid $6 each for two rooms.

I asked for a room with a desk and plopped down the Underwood typewriter I’d bought at a garage sale. I pulled out a tiny artificial Christmas tree from my backpack and set it on the scarred dresser.

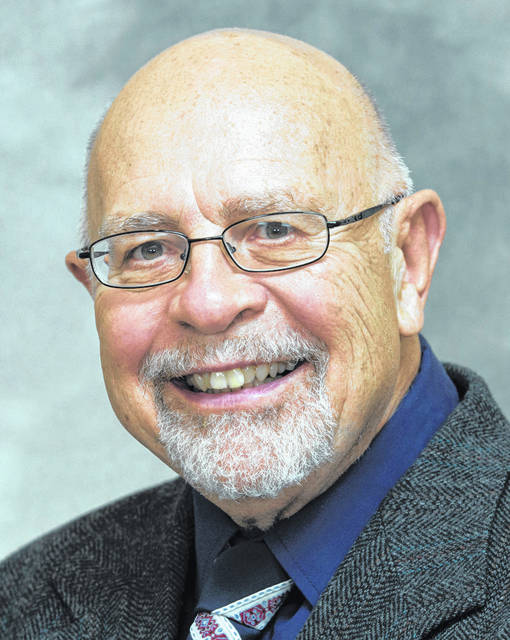

Max left the Open Arms in search of a bar’s small talk, while I hunched over the Underwood to write the “Sheepstress of Gobbler’s Lookout” story. About 3 p.m. I was on a roll writing when Max opened the door and photographed me in my undershirt pecking away at the Underwood. Above me a bare bulb hung from the ceiling. Max sold that photo of a freelancer at work to “Writer’s Digest.”

“You won’t believe all the people downstairs,” Max said. “A bus is stranded here overnight.”

I put the typewriter in park and followed him to the lobby. I saw numerous male and female drifters wearing denim, an elderly couple, and a worn-out woman in her 30s with a small boy. The driver and affluent passengers had elected to sleep in a pricier chain motel.

The owners of the Open Arms, a pregnant earth mother and her longhaired husband, addressed us all. They told us they had planned a communal Christmas meal in their apartment.

“It will be a pitch-in,” Earth Mother chirped.

The invitation cheered us. I salivated, weary of microwaved sandwiches in cellophane. I smiled at the boy. He looked at the floor.

Max and I trudged through the snow-deep streets to a grocery store to purchase canned goods and Boone’s Farms wine for the meal.

We then went back to the restaurant gift shop and looked for something to give the kid. I’d already given my own son his presents at an early Christmas.

Max and I returned to the Open Arms to clean up in the communal bathroom and to don clean shirts. We removed our Stetsons as we entered the apartment. We sniffed the aroma of apple and pumpkin pies cooling on window sills.

Bus passengers created a makeshift dinner-table extension out of plywood and a sawhorse. Earth Mother oversaw the cooking of the turkey, while her husband baked Montana trout.

The owners put Max and me to work, setting dishes, silverware, and napkins on the table. The guests chatted, talking about destinations and personal stuff we’d have kept from anyone we knew well. The tired woman told me her marriage had exploded. She was taking her son to live with her parents. I watched her boy study her worn face.

The turkey leaked juices through parchment skin, and the trout baked. Max lifted a glass and toasted our hosts. After one scrumptious bite finished, I shoveled in the next.

Following dinner, we washed dishes to clear the post-feast debris. “Carols?” suggested a drifter with a guitar.

“Silent Night,” the inn owners requested. My favorite carol sounded beautiful although most of us sang off-key.

The boy’s sweet voice joined our rough baritones. After the song, I handed him a wrapped T-shirt. Other guests gave him spare change and whatever passed for gifts. His grin warmed us, blessed us, as he tore paper from presents.

The stranded guests took whatever goodness was left in them and gave joy to a boy in need of Christmas.

The boy, the meal, and the post-dinner filled wine glasses made the occasion sacramental. The night wasn’t silent, but the night was holy.

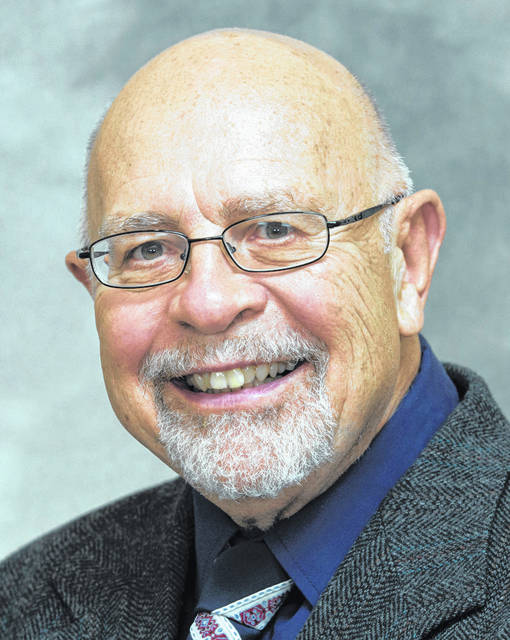

That boy must be 50 now in 2020. Max shoots photos for “National Geographic.” My wife Gosia and I enjoy retirement in Union City. We went to Harter Park for the Christmas Lighting ceremony and stood on the street to wave at the cars in the parade.

I hope that boy and his sad, sad mom lived equally blessed lives.

“Christ, the Savior, is born.”