Labor Day, a national holiday that celebrates the American worker’s significance and achievements throughout the U.S. and her territories was signed into law by President Grover Cleveland on June 28, 1894. The Uniform Monday Holiday Act of 1968 changed several holidays, including Labor Day, so that federal employees could have more three-day weekends.

Metro Media image

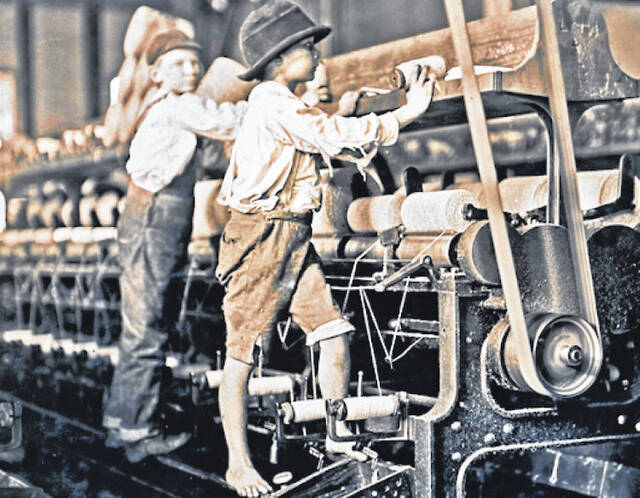

Child laborers working in southern textile factory, taken by twentieth century photographer, Lewis Hine. Hine, an investigator for the National Child Labor Committee, traveled across the country documenting child labor practices in the early 1900s.

Lewis Hine | U.S. National Archives

By Carol Marsh

DailyAdvocate.com

GREENVILLE — Over the years, many people have fussed about whether or not to ditch the white clothes, shoes and purses after Labor Day. However, this somewhat bizarre fashion trend — of removing these summertime linens and seersucker jackets from our wardrobes — seems like a seasonal rite of passage, marking the end of carefree summer leisure with a return to school and the regular rigors of the work week. Yet, the “origin story” of Labor Day is an uncomfortable journey through a difficult corridor of our nation’s past — one that we should take time out to remember this weekend.

Labor Day was established as a direct response to the civil unrest of the 1880s, during the height of the Industrial Revolution. The average American worked a minimum 12-hour day, seven days per week, with children as young as five or six years old, expected to work factory, mill, and mining jobs to provide income to help sustain their family’s household. Children, who worked alongside their adult counterparts, were especially vulnerable, as they were expected to do the same day’s work, while receiving a faction of the wages.

Most egregious was the earlier “free” labor movement, in which former slave children were functionally “re-enslaved” through so-called “apprenticeship” agreements, wherein parents unknowingly exchanged the child’s labor in return for industrial “training” provided by the former slave owner. While many of these free labor “apprenticeships” were remedied during the Southern Reconstruction, such abusive practices continued to the North, particularly in New York with the operation of the padrones (persons who secured employment for Italian immigrants). Italian parents were deceived into signing “apprenticeship agreements” with the padrones, who offered to teach the children music while living in America. Immigrant children were forced to work as street performers, and often beaten if they did not hand over their “earnings.”

While in 1870, one out of every eight children was employed, this rate increased to one out of every five children by 1900. Between 1890 and 1910, 18 percent of the American workforce was comprised of children under the age of 17. Men, women and children alike, many of whom lived in poverty, were subjected to unsafe working conditions, with insufficient access to fresh air, sanitary work facilities, and breaks. In the mid-1880s, workers began to protest against these unfair labor practices and conditions, organizing strikes and rallies, in an attempt to force employers to renegotiate wages and time. Many unsettling encounters ensued, including the infamous Haymarket Riot in Chicago, 1886, which killed police and workers, as well as the May 11, 1894, Pullman Palace Car Company strike. The ensuing American Railroad Union boycott, led by Eugene V. Debs, caused the U.S. government to dispatch troops to Chicago in order to break the strike, and dozens of workers died as a result.

To quell the ire of the working class, Congress enacted legislation to honor the American worker’s significance and achievements throughout the U.S. and her territories with a special day — Labor Day — which, on June 28, 1894, was signed into law by President Grover Cleveland. The Uniform Monday Holiday Act of 1968 changed several holidays, so that federal employees could have more three-day weekends.

So, in this imminent change of seasons, whether we choose to don white jackets, purses or shoes before, during, or even after Labor Day isn’t nearly as important as remembering that without these dedicated workers — in factories, shops, mills, and plants worldwide — we wouldn’t have those jackets, purses, shoes (and other things) that we just can’t seem to live without.

Carol Marsh covers community interest stories and handles obituaries for Darke County Media. Have an event to share? She can be contacted by email at [email protected] or by phone at 937-569-4314.