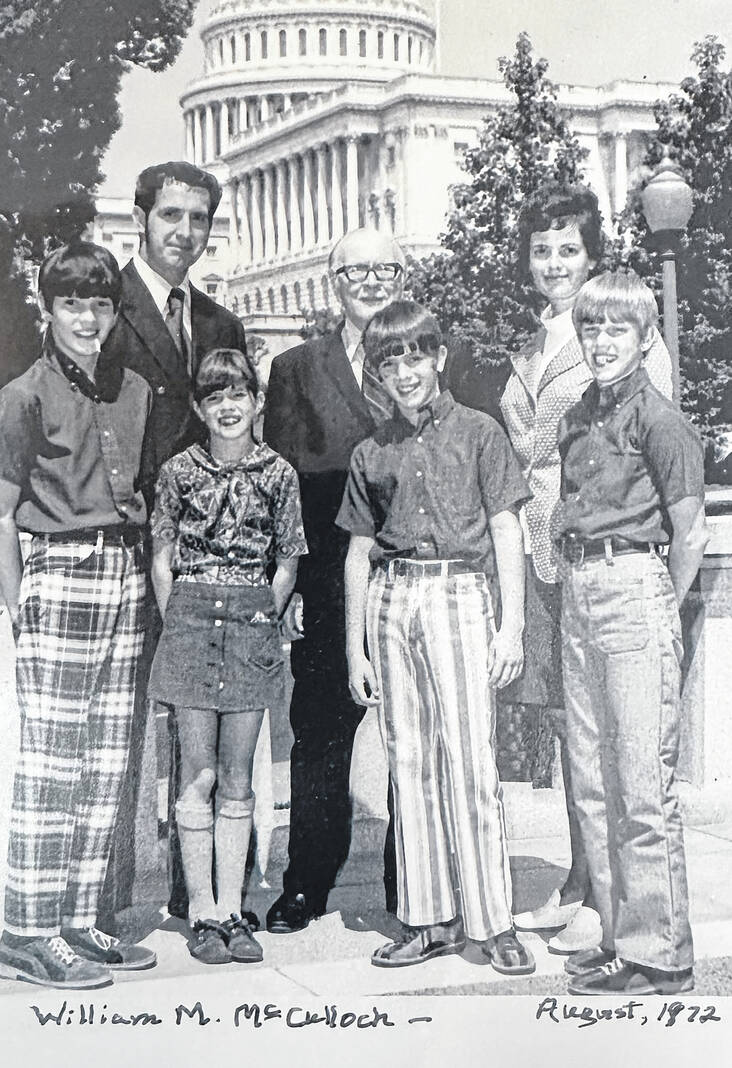

The Paul Gutmann Family at the Capitol with Wm. McCulloch; Paul and oldest son, Michael (left) worked with McCulloch.

Submitted photos

William Moore McCulloch

Submitted photos

By Vivian Blevins

Contributing Columnist

How many Americans can you name who are known for their commitment to civil rights? Can you specify the ways in which they turned their beliefs into positive actions? Ask yourself what the results would be if you conducted a moral inventory of yourself regarding your belief system and civil rights.

Is the name William Moore McCulloch (1901-1980) on your list of Americans who have worked on behalf of civil rights? Do you have a fuzzy sense of who the man was? Have you been to the Piqua Public Library where his statue is located out front? Or have you noticed signage at an establishment on Main Street in Piqua by the bridge over the Great Miami River that reads The Randolph and McCulloch Freedom’s Struggle Complex?

Do you have an understanding of why the names of two white men would be connected with a struggle for freedom? John Randolph of Roanoke, Virginia, (1773-1833) served in both the U.S. House of Representative and the U.S. Senate, and owned almost 400 slaves at the time of his death. And McCulloch was an attorney who served in the U.S. House of Representative from 1947-1973.

Randolph wanted his slaves freed after his death. And after relatives were involved in much wrangling over his wills, the freedmen journeyed to Mercer County where Randolph had purchased land for them. There, they were turned back into their canal boats by hostile residents, and some settled in Rossville, outside of Piqua. And McCulloch? He is known for his role in the House of Representatives in working tirelessly, and with tremendous political savvy, to shepherd civil rights legislation to passage.

What do area Miami Valley residents have to say about McCulloch?

Retired Piqua High School teacher of Black history from 1971-2001, Larry Hamilton says, “McCulloch was an extraordinary man. He was not a man of the moment: His moral compass would register the same TRUE direction today as it did in the era of Civil Rights- to lift his voice in condemnation of the current lies and misinformation. These falsehoods undergird authoritarianism, a real threat to democracy. It’s important that we educate people today of the stance McCulloch would take were he alive.”

One person who understands what McCulloch’s position would be if he were still alive and how he would approach bringing about positive change is Jim Dicke, president of Crown Equipment Corporation. As a student at Trinity University in San Antonio, Dicke served as an assistant to McCulloch in the summers of 1966 and 1967. Dicke says, “When I worked with William McCulloch, he had already played the major role in getting the Civil Rights and Voting Rights through Congress and was working on Open Housing legislation.

“At that time, if the ranking member of a committee wanted to do something, the other members of the caucus were generally supportive. Also, Republicans were more in favor of Civil Rights legislation than were southern Democrats, the grandsons of those in the South who were committed to states’ rights on voting and who had endorsed Jim Crow laws.”

Why was McCulloch supportive of civil rights? Dicke reports, “McCulloch had been raised on a farm in Ohio, and his ancestors were passionate abolitionists who had helped with the Underground Railroad. As a graduate of the law school at The Ohio State University, McCulloch’s first job was in Florida where he saw segregated facilities for the first time and the atrocities that Blacks endured. He and his wife Mabel were there for two years at a time when real estate was booming. This meant, of course, that desirable lands, long inhabited by African Americans, had suddenly become valuable real estate.”

For a quick analysis of the deplorable history of racism in Florida, one source is The Washington Post, Jan. 21, 2023, Lori Rozsa’s feature: “A Black professor defies DeSantis law restricting lessons on race.” Rosewood Massacre, lynchings, murders, and bombings.

Dicke indicates what he learned about “constituent service,” the philosophy that undergirded McCulloch’s sense of his role in Congress. Be a listener. Help those who come to you with their problems. If you can’t help them, work to let them understand why you can’t so that they don’t feel frustrated, unheard. He also indicated that McCulloch felt that a legislator should not ask others to do something that he would not do himself.

When McCulloch was asked whether he was liberal or conservative, he would respond, “On what subject?” He realized always that absolute allegiance to a political platform is not a course of action that he could endorse.

Further, Dicke indicates that if McCulloch disagreed with another congressperson, he knew there was a whole district of voters that had elected this person as their voice, and he needed to listen.

The strategy for legislation, per work on Fair Housing that Dicke observed, was as follows: (1) Draft a piece of legislation; (2) Listen for comments from other congresspeople, from voters in the home districts. Know that listening to the opposition is important because in writing the draft, the authors might have overlooked something; (3) Amend the original draft as necessary; (4) Don’t put it up for a vote until you are certain you have the requisite votes for passage.

Dicke was true to McCulloch’s sense of the role of legislators and legislation as he paraphrased a philosophy of a man who wanted to “hammer out on the anvil of public debate a compromise between polar positions” to an acceptable compromise to the majority and not pass legislation with a dictatorship of 51 %.

In October of 1971 McCulloch said, “We are a nation of many voices and many views. In such a nation, the prime purpose of a legislator, from wherever he may come, is to accommodate the interests, desires, wants, and needs of all our citizens. To alienate some in order to satisfy others is not only a disservice to those we alienate, but a violation of the principles of our republic. Lawmaking is the reconciliation of divergent views. In a democratic society like ours, the purpose of representative government is to soften tension-reduce strife-while enabling groups and individuals to more nearly obtain the kind of life they wish to live.”

In an interview in 2020, Dr. Paul Gutmann indicated that a memorable part of working in William Moore McCulloch’s law office was during the Civil Rights movement of the sixties, “This was a very divisive time in American history, and Bill McCulloch stepped right in and did what was necessary to ensure the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, getting the Republicans to go along with that.” Gutmann also indicated at that time that John F. Kennedy is alleged to have said of McCulloch and Civil Rights legislation, “Without him, it can’t be done.”

Gutmann’s oldest son, Michael Gutmann, is a graduate of the University of Miami and the University of Cincinnati College of Law. He says, “When in 1984, I returned to Piqua to join with my father in the law firm founded by William McCulloch, I wanted to learn more about this man and turned to Charles Whalen’s book The Longest Debate. This volume gives an account of the filibusters in the U.S. Senate who threatened to make certain that Civil Rights legislation could never garner the necessary votes for passage.

He relates the story of 1945 when there was a sit- in at the lunch counter at the bus station in Piqua. McCulloch was working with the NAACP and Black residents Emerson and Viola Clemens to inform them of their constitutional rights as citizens. They won that one.

Gutmann noted that McCulloch had worked with President Dwight Eisenhower through the late fifties on Civil Rights legislation and was determined, as was President John F. Kennedy in the sixties, to get it passed.

Gutmann indicates that “McCulloch, as the ranking member of the Judiciary Committee, was a leader respected by his party as well as by northern Democrats. They had experienced failures in the past with the contentious issue of Civil Rights legislation, and McCulloch knew that legislation, moderate in scope, was essential and that it would be impossible to get passage for all that the Black caucus wanted included. It was necessary to ensure equity in terms of public accommodations and take individual businesses off the table.”

Gutmann reports that McCulloch had a small staff and worked hard at all the tasks of his office, including preparing materials for mailing. He always assumed a low profile, and his positions were never intended to promote his career: He believed that what he did was the right thing to do.”

He continues, “Bill McCulloch liked to talk with the people on the streets as a way of finding out what they thought of Washington. He would ask, ‘Anything you don’t like? Anything we can do to improve things?’”

In 2009 the issue of Ohio’s representation in the National Statuary Hall arose. Gutmann says, “William Allen, former Ohio governor and Congressman from Chillicothe and pro-slavery advocate, was considered inappropriate to represent Ohio in that hall. Ohio decided to let the people put forth another name. Assassinated former president James Garfield would remain as the second person representing Ohio. Names such as the Wright Brothers, Jesse Owens, Harriet Beecher Stowe and Thomas A. Edison were nominated, along with William McCulloch.

“Ohioans Jim Dicke; Walter Fauntroy; Jim Oda; and Colleen McMurray, daughter of Emerson and Viola Clemens; and Michael made a presentation before the committee of U.S. House of Representatives that would make the decision. Although Edison was ultimately chosen because of his many inventions that changed the lives of Americans, the advocates for McCulloch raised his profile to such a high level that he received many honors, including having his papers placed in the Congressional Archives in Columbus.”

Of special note in the hearings was African American McMurray (born in 1930) who spoke of her years of growing up in Piqua and “feeling different” because as Gutmann reports “not being able to swim in the community pool or play golf or eat at local restaurants, of how the lives of all Blacks were negatively impacted by the laws of the day.”

In the McCulloch Archives in Columbus is a letter to McCulloch dated June 4, 1971, from Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. In it, she writes, “I know that you, more than anyone, were responsible for the civil rights legislation of the 1960’s and particularly for the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

You made a personal commitment to President Kennedy in October 1963, against all the interests of your district.

When he was gone, your personal integrity and character were such that you held to that commitment despite enormous pressure and political temptations not to do so.

I think of President Kennedy’s Profiles in Courage. You were a conservative Midwestern Republican from a farm district, who by seniority found yourself in a position where the civil rights problem was thrust upon you. Your integrity under such pressures is what makes our political system worth fighting for and dying for.”

In conclusion, there is person who continues the fight and offers advice, Barbara Davis of Piqua. Davis, a graduate of Duke University and the University of Dayton and a U.S. history and government teacher from 1983 to 2008 at Piqua High School, knows more than a bit about congresspeople and legislation. While her husband was in law school at Georgetown University, she worked for three years on Capitol Hill for Louisiana congressperson Joseph David Waggoner, Jr.

In that role, she answered correspondence for Waggoner after first consulting with his legislative assistant to ascertain Waggoner’s position. Also, Waggoner had his assistants keep a personal file on many of his constituents so that they- and he- could personalize the correspondence. In her role in that office, she was knowledgeable of the agencies so that she could refer those Waggoner represented to the proper places to address their issues. Before signing, Waggoner always read the correspondence to be mailed under his name, and if there were mistakes, he tore the letters up and placed them on his desk. Luckily, this seldom happened.

Davis’s father, Robert Fite, was an attorney with McCulloch’s law firm in Piqua, so from an early age, she has been interested in political science. As a teacher, she made certain that her students did well at regional and state competitions for Ohio History Day. Currently, she endorses the need for citizens to proactively seek to learn from other cultures, and she has several recommendations. One is to invite persons of diverse points of view, races, ethnicities to speak at organizations. As a weekly volunteer at Springcreek Primary Elementary School in Piqua, she understands the need for young children to learn to be inclusive at an early age as well as the need for area citizens to be involved in using their talents and time in volunteering. Further, she recommends volunteering at places such as the Bethany Center and attending events that sponsor diverse speakers and are committed to equity such as the YWCA, the Piqua Public Library and Edison State Community College.

Finally, what actions do you plan to take to educate yourself and to use your talents and time to further the legacies of Randolph, McCulloch and others?