Near Darke

By Hank Nuwer

Corporal Hugh Lincoln Armstrong huddled with other shivering U.S. troops on December 15, 1944. They were in western Luxembourg one day before Adolph Hitler’s seasoned Panzer troops launched a deadly counteroffensive of the Battle of the Bulge.

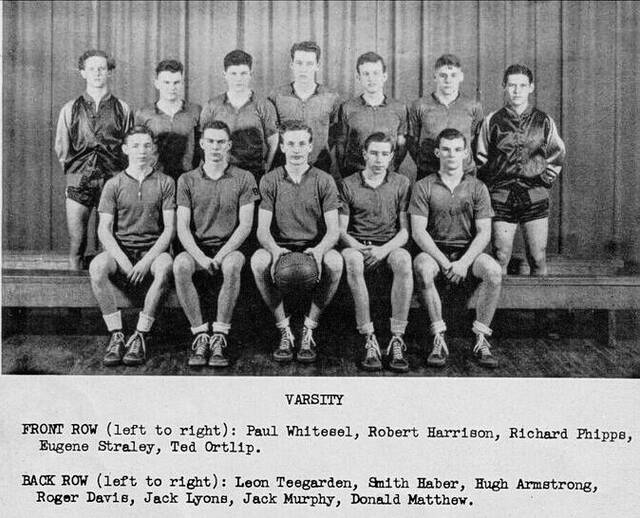

Armstrong had been a catcher on the Union City (IN) high school’s baseball team and a member of the basketball team before dropping out. The army assigned him duties with a tank destroyer outfit. He was last-home on a 15-day furlough in midsummer ’44.

He shipped out December ’44 and, after a sojourn in England, took his position in thick, snow-blanketed woods. His superiors assured him this was a cakewalk. No heavy fighting was expected.

However, Army intelligence had blundered. Germany planned an all-out attack against undermanned and spread-thin U.S. troops.

It was one of the coldest winters on record in the Ardennes Forest.

The miserable weather lasted, grounding protective aircraft that might have saved the lives of many Allied soldiers.

That December 15, a a C-64 Canadian Norseman landed at an English air base. He was there to collect band leader Glenn Miller and an army officer serving as Miller’s aide. They planned to entertain troops in newly liberated Paris.

Captain Glenn Miller gave his all for the war effort. Before leaving for Europe, he raised millions for war bonds by staging concerts in swing style.

The temperature was right at the freezing point when pilot Johnny Morgan, a USAAF flight officer, helped the two passengers board. Morgan told Miller he could navigate the soupy, freezing weather using the plane’s instruments.

The band’s manager, Don Haynes, begged Miller to reconsider.

“This weather would even ground a healthy bird, but I’ll go anyway,” Miller said.

Miller ordered Haynes to accompany the 60-member big band after the weather cleared. Three days later, Haynes and the orchestra landed in Paris in better weather. The manager learned the C-64 never arrived. The plane likely had iced over in the air and plummeted into the English Channel. All three men aboard were lost.

Over in the massive Ardennes forest, Armstrong and his buddies cursed the cloudy, foggy sky swirling with snowflakes. They groused that this was “Hitler’s weather.”

On December 16, the Nazis attacked. Shells exploded everywhere. Armstrong’s foxhole offered inadequate protection. Thousands of men fell and thousands of men were captured in mere days.

On the 17th, Armstrong’s unit surrendered. The Germans frisked the prisoners, taking candy, gloves, cigarettes, and sometimes precious boots. The Germans cursed and ridiculed the POWs as “Chicago gangsters.” They had watched too many Hollywood movies.

After a long, torturous march in the snow that saw wounded prisoners drop and sometimes executed, Armstrong and forty-some other soldiers crowded like sardines into a box car. It would be days before their captors tossed them stale bread and cheese. The boxcar stank of cow and horse dung. Sleeping was torturous. Human slop was collected in helmets and tossed through a narrow opening in the boxcar.

Finally, he arrived at Stalag 4-B near Muhlberg in east-central Germany. It would take one month before Hugh’s parents received a war department telegram informing them of his capture. A postcard courtesy of the Red Cross reached his parents in mid-March. Hugh said he was okay and requested a pipe and tobacco.

But he was not okay. Food was limited to a thin potato soup and moldy bread. Guards dished out abuse. He and his fellow prisoners talked about mom’s cooking, American cars, their girlfriends and brides, and an end to this blasted war.

On April 23, U.S. troops stormed the POW camp, while Russian troops marched in vast numbers toward Berlin.

Corporal Armstrong was free but in need of hospitalization in France. He had lost weight and had not had a shower or changed clothes since his internment.

At last he arrived safely in Union City. Friends threw him a party on August 24. Hugh’s superiors informed him he had been promoted to sergeant. He re-enlisted. He became a career soldier the end of ‘45.

When the Korean conflict broke out, Hugh was in the thick of action. So nobly did he fight, Army brass awarded him a Bronze Star.

After the truce ended the bloody Korean conflict, Hugh shipped back to the states. He happened to be the first combat soldier to step off the ship. Stunned, he faced a mob of reporters clamoring for a statement. Hugh said it was good to be home.

Hugh served 20 years in the military, relocated to Olympia, WA, and then began a second career as a landscape supervisor for the state of Washington. He retired December 30, 1984, and died too soon on January 11, 1985.

Consider today’s column a sincere thank you to Hugh for his honorable service.

Hank Nuwer is an author, columnist and playwright. He and wife Gosia live on the Indiana side of the Union City state line. Viewpoints expressed in the article are the work of the author. The Daily Advocate does not endorse these viewpoints or the independent activities of the author.